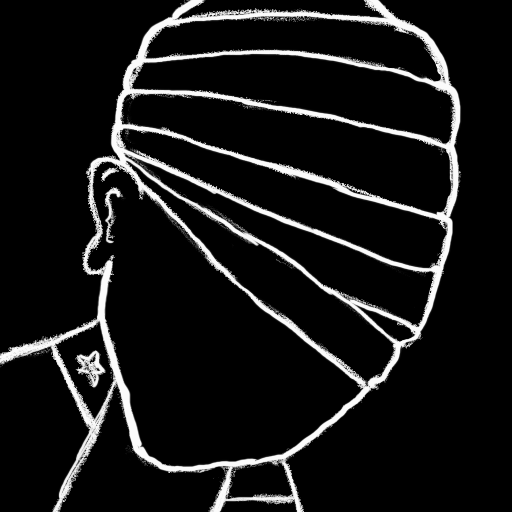

Faceless

Who am I? And why was I not mentioned along with the others?

I am special. They call me “Archivist”, but then that leads to the question of who they are, and who I am is far simpler.

To the trashman I wear a white coat, reminiscent of the laboratory coat of a television scientist, something he may have seen in passing while flipping through the channels late at night, searching for something to put him to sleep. My eyes hide behind greasy glasses, and my balding head clings to its last fraying wisps of white hair that blow askance in the slightest breeze. If he looks closely at me, which he does only once, the trashman notices that the bottom of my lab coat is filthy, as though it has suffered the indignity of being dragged along the floor. Yet it fits and is short enough to reveal my naked old-man ankles and drooping socks that spill over the sides of my shoes like gray blobs of melting ice cream.

To the scientist I’m an average-looking businessman in an average-looking suit, clutching a battered black briefcase to my chest like a shield. I tremble constantly, and a slick sheen of sweat plasters my lanky black hair to my brow. I have small darting eyes, and I’m always panting as though I have run a few miles in the sun. When we sleep together that first night, she notices that the briefcase is secured to my wrist by a pair of handcuffs, one loop clasped through the case’s handle. She wants to ask me about it, but never gets the chance.

To the housewife I’m a solider much like her husband was, dressed in a uniform that is vaguely familiar yet altogether alien. She spends a great deal of time trying to identify it, and finally convinces herself that it is Soviet. It is not Soviet. My head is bandaged in bloody ropes of loose gauze that cover my eyes and nose. Because of her conviction about the uniform, she does not approach me to see how I am doing, though her basic human instincts urge her to do so. She wants to tell the others not to talk to me and feels nothing but internal conflict whenever she notices them with me. It is of supreme interest to me that she does not recognize the mouth and jaw of her dead ex-husband.

To the politician I am a familiar prostitute, one that was supposedly “taken care of” at his behest prior to his run for governor. Or am I just one that looks like his victim? In a certain light, the resemblance is striking. Other times I appear as an entirely different person. In all forms I excite something primal in him, and he gets angry with himself and his erection. That rage grows until it reaches the point where he is convinced that he must do something about me before he can attend to his other problems. In this way I have played the role of provocateur perfectly, as the drama arises simply from my being there.

To the artist I am a long-dead poet she boarded with in her college years. I am a literal ghost. She does not want to acknowledge my presence and refuses to believe that I exist. She has been doing this for a lot longer than the time in the cell, ever since she got her first cheque from the publisher for the little book of poems that she did not write. She has been seeing me everywhere since that day, and without drug or drink to escape to I am driving her mad.

Who am I?

I am the catalyst, and the observer.

I am a blank slate.

I am the instigator.

First draft: 150327

Published: 231018