September 2010

September 9, 2010

Recently Acquired for Week 36 of 2010

Recently Acquired was a Dark Acre “feature” where I reviewed the first 5 minutes of any new games I’d either impulse-bought, pre-ordered, or just straight-up enjoyed. Ironically, as of summer 2025, I’ve beaten none of these. –Ed

Terry Cavanagh’s “The Letter V Six Times”

I played this game back when it was just a proof-of-concept that Mr. Cavanagh released to the web for feedback and testing purposes, and at the time it was the first game I’d seen or played with the gravity-switch mechanic.

In the time since that release and this official version he’s polished it to perfection. I remember reading an article some time ago about how so many games only explore the surface of their core mechanics, and how games that take their mechanics to their full logical conclusion tend to fare better for both initial enjoyment and long-term play.

The Letter V Six Times is the gravity-switch mechanic taken to its logical conclusion. Sure, Cavanagh’s managed to dress it up nicely with the retro-inspired graphics, ear-watering 3D 8-bit-esque audio, and a cute/clever story, but the heart of it is jumping from floor to ceiling and not killing your hapless avatar in the process. And it’s fun.

It’s a game that induced sweaty palms several times in few minutes I played, much as the PoC did all those months ago, and while it can be frustrating the challenges presented are not insurmountable but do require a bit of patience and respect for the “do it again, stupid” learning mechanism. Well worth the Steam price, I do want more than the 5 minutes I’ve given it.

Frictional Games’s “Amnesia: The Dark Descent”

From the makers of Penumbra comes the next iteration in their immersion-horror concept, Amnesia. I have to confess to have given more than 5 minutes to this game, and that can only be a good thing. Much like the stellar Dead Space, Amnesia must be played in a darkened room at midnight with headphones on. The gamma settings must be calibrated so that you can’t see a thing, and you’ve got to play it without worrying about saving or loading or any other meta-game nonsense. This game is frightening.

Now, as a game developer with knowledge of how games are built and presented (much like a filmmaker knows all the behind-the-scenes trickery involved in a movie) I know that this is just a collection of audio cues, 3D models, and post-processing effects. Yet even with this knowledge hanging over me, ever ready to dispel the illusion, I was scared out of my mind. Frictional has managed to assemble Penumbra in a perfect, non-clichéd, totally fresh way that will keep even hardened survival-horror gamers on the edge of their collective seats.

If you want to be terrorized and enjoy a few sleepless nights, Amnesia is a steal at 20 USD on Steam.

Standing in the dark will reduce your sanity.

EasyGameStation’s “Recettear: An Item Shop’s Tale”

Irrashaimase! Can anyone tell me if EasyGameStation is a Japanese developer? Because if they’re not, they’ve done an impeccable job of crafting a Japanese role-playing game.

If you’re familiar at all with the classic J-RPGs like ChronoTrigger, Final Fantasy, or Dragon Quest, you’ll feel right at home with the setting and characters of Recettear. While the text is all in English, the characters have Japanese-language sound cues, reinforcing the tone of the game.

So, what is Recettear exactly? It’s an RPG where you play as the owner of an item shop. In the five minutes I’ve given it I woke up, got briefed on the mechanics of the item shop, met with a guild leader, and picked up my first round of inventory. Is it compelling enough to keep me going? Absolutely. If you like cute, as in syrupy-thick-Japanese-anime-cute, and you’re a fan of classic J-RPGs, you will love this unconditionally. The music perfectly accompanies the setting, and it really feels “fun”. I hear there’s monster-battling and a bunch of stat-driven leveling up to do, and I’m looking forward to finding out what that’s all about.

This one’s also available on Steam.

All three of the games in this Recently Acquired have demos, so if any of them have piqued your interest don’t just take my word for it, download them and check them out for yourselves.

September 13, 2010

Real Wisdom: Part 1: Planning

Originally presented a three-part series. –Ed

Plan

I am guilty of wanting to jump in with both feet before checking the depth of the water or whether or not it’s shark-infested.

Some say it’s the hallmark of the adventurer, the entrepreneur, and the brave. The sad reality is that it’s the hallmark of the short-sighted fool. If we get lucky, and we don’t hit any rocks or end up in a shark’s belly, it can be a fun experience. The trouble is that the one time we crack our skulls on unseen stones is enough to cancel out any fluke successes we got the times before.

I’ve found that the longer I stay in a given industry (and I’ve been in a few now: food service, education, and game production) the more I see the older and wiser laborers always working from a meticulously crafted plan.

So why plan? Why not be spontaneous, wild, and free? Screw planning, it’s too much like rules. Or worse, it’s too much like work.

Here’s a reality check: planning is the stage where we’re supposed to go wild. It’s the only place where we can throw out the rulebook and see what sticks to the walls. It’s the place to think outside the box and go off on insane and impossible tangents. Here a person could spend years dreaming and wandering until they’re satisfied they have enough of a foundation to start building.

If it’s one solid truism about production that I’ve learned in the past 12 years, it’s that nothing beats a solid plan. Sure, it’s impossible to plan for everything but planning for nothing will usually result in nothing, and we’re going for tangible results here.

September 15, 2010

Real Wisdom: Part 2: Executing

[Lost content, likely a thematic image for “execution”.]

Execute

Once we learn to resist the urge to leap into production without any clear goals, and can sit down and hash out reasonable strategies for success, it’s time to start making things happen.

I lived and worked for 10 years in Tokyo, Japan, and in that time I was inundated by the Japanese mentality to approaching work: marathon, not sprint, requiring a steady and careful use of resources to produce a winning run. By its very nature this causes people involved in projects to take a longer view, and try to see further into the future than the end of the next task.

Having a structured system of objective-driven goals and the means to measure success is just as critical as knowing what and where the finish line is. We have to take a supermassive target (launch a game), break it down into its component parts, the order they need to be assembled in, and estimate the available resources for each section!

This illustrates the importance of careful planning, and how (solid) execution ends up being a very short cycle in the development process. Everyone involved in production needs to know where they’ve been, where they are, and where they’re going.

I would never advocate slavishly following a plan in game development. As a creative endeavour, the execution strategy has to allow room for the inevitable scope changes that will occur during production. A savvy project manager will allocate time for feature refinement and improvement, and squash scope changes that would reduce the success chances of launch. Creatives that feel like there is breathing room will appreciate the ability to voice any concerns that arise and make necessary adjustments to the design.

September 17, 2010

Real Wisdom: Part 3: Results

Results

There really isn’t much to say about results: the how and why are determined by the depth of the planning and the quality of the execution.

Many failures to achieve the desired results find their roots in poor planning (rushed, incomplete, unrealistic) or lackluster execution (non-communicative, passionless, without vision). The results of a given project are the final measurement of how well the preparation and labor were carried out.

The purpose of this series isn’t to give best practices for successfully completing projects; rather it’s to remind that any undertaking can be broken down into basic component parts, and that each of those parts has to be given the time and care it requires.

In the business of producing a game, this is especially critical. We undertake a highly creative endeavor and attempt to turn our art into product (at least, those of us that still rely on things like money). To achieve any measure of quality in our results we need to realistically plan and then passionately execute our visions.

September 27, 2010

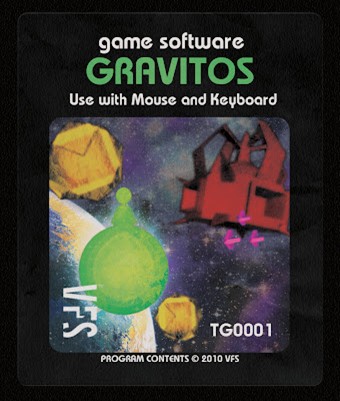

GRAVITOS, and the Era of Transition

My student life is nearly officially done. The three-man project we were doing finaled this past Friday at 4 PM, a full 8 hours ahead of the deadline.

Every goal I set out for myself on that project was reached, and in some cases exceeded far beyond my expectations. My two teammates, Darryl Spratt and Bernard Hwang, deserve the lion’s share of credit for producing a fully functional game and platform with very few resources and an incredibly restrictive schedule.

If you’re interested in playing the game, you can download Gravitos here. (Internet Archive link, just to show it once existed. Now defunct. —Ed)

So, what does this all really mean for me, and Dark Acre Game Production? It means that, after 7 long years of saving, studying, and surviving, I can finally focus 100% of my attention on producing my first independent computer game.

I started pre-production last week and have been using every spare minute to work out a design that satisfies me enough to go to engine. I’ll be using Unity 3D to deliver the game, and production won’t go past the end of December. I’m planning on having three, four-month production cycles per year, either ending up with three published games or three versions of a published game, or some combination of iterated and new design.

I’m also writing in earnest, for the first time in my life I’ve finally got the work schedule I want, and this means time for physical development, authoring a novel, and producing a computer game. Dreams can come true with enough hard work and dedication.

2010.09.01 – 2010.09.30